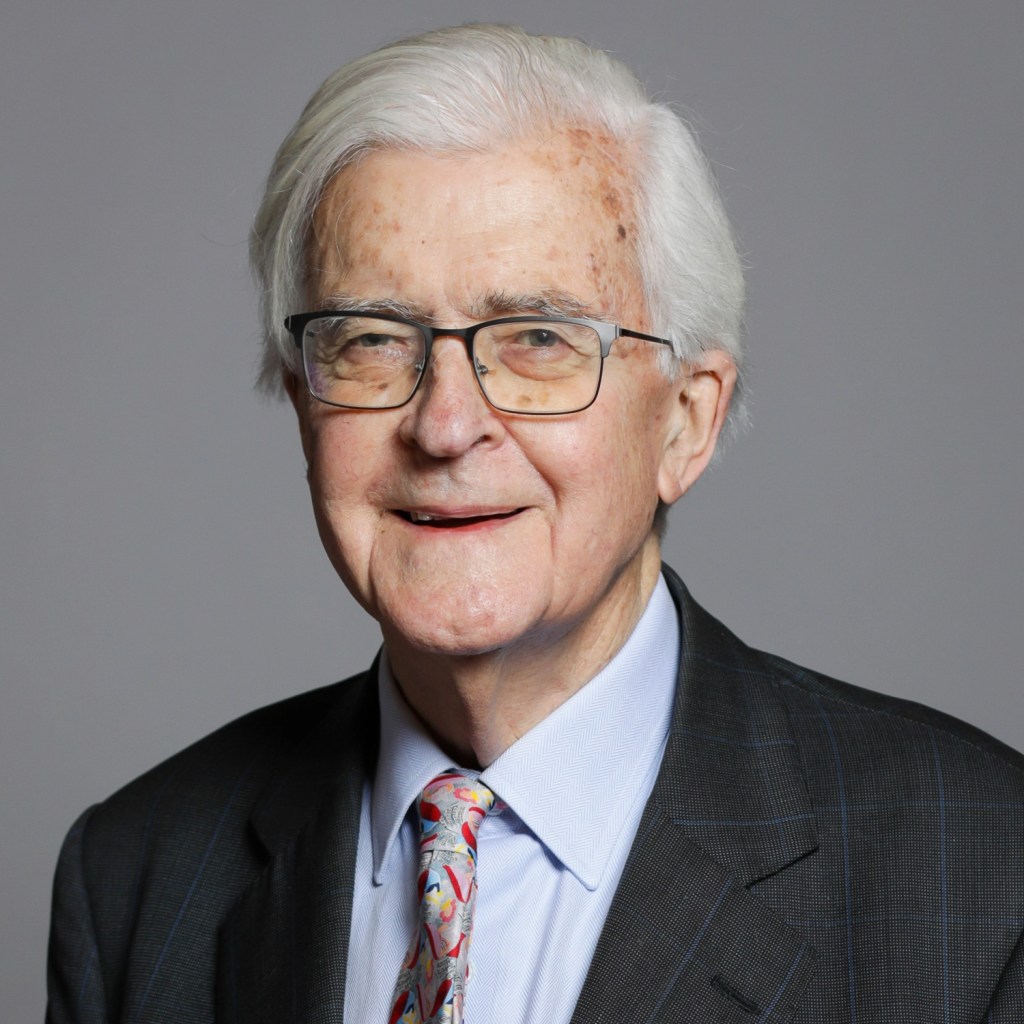

Former New Labour education minister David Blunkett and Kenneth Baker, architect of the National Curriculum under Thatcher continue to sound alarm bells on the government’s plan to scrap popular vocational and technical qualifications in England and push students into taking new T-levels.

Supported by former Tory University ministers David Willetts and Jo Johnson, also members of the House of Lords, they are concerned that the latest guidance from the DfE on the withdrawal of funding for qualifications with content that overlaps with T-levels, rather than affecting a ‘small proportion’, may turn into a cull and include many of the popular Level 3 BTECs. In a letter to the Secretary of State, Blunkett and colleagues (in the context of Jeremy Hunt’s recent claims about poor productivity) argue these qualifications “play a vital role in developing the skilled workforce of the future”.

Their Lordships have a questionable understanding of skills needed for work. To begin with, many of the ‘middle’ or intermediate levels jobs (in offices, at technician level and shopfloor ‘craft’) for which vocational and technical qualifications were designed no longer exist – the increased use of automation, while not the only factor has been a significant cause of this. The occupational structure has polarised with professional and managerial jobs at the top, (though not enough for the thousands of graduates qualified to do them) but with more and more people being pushed down into ‘precariat’ and lower paid employment. Also, many skills continue to be learnt ‘on the job’.

They also overemphasise the role played by technical qualifications in promoting social mobility. Though it has to be recognised that BTEC type qualifications also play important roles for many young people in securing university places, they are not generally accepted by Russell/ Oxbridge type institutions. It’s also the case that newer universities have looked to recruit BTEC students, so as to ensure courses are filled.

But the longer-term implications of an ‘A or T’ bipartite post-16 qualifications system are dire. It will short circuit, or at the very least, make further curriculum reform extremely difficult. There will be no bridges to connect the two routes, as many smaller qualifications that students have used alongside academic or vocational courses, are also likely to lose funding. In addition, many of the 200 000 students on level 3 BTEC style courses are only registered for a single unit: equivalent to one A-level and therefore able to also be combined as part of a UCAS application.

There are other genuine concerns about T-levels. Blunkett ( in comments to the Guardian 29/01) is right to fear that the widespread scrapping of qualifications from 2025 could ‘backfire’. The new qualifications are in the early stages of development and still will be when the funding for alternatives starts to be withdrawn. The size, the complexity and the work placement requirements of T-levels will make it difficult for smaller providers of post-16 education, particularly school-sixth forms, to deliver them. (Huge numbers of Year 11 students opt to stay in their school sixth forms where they can, often to be with their friends, rather than make uncertain transfers to out of neighbourhood FE colleges.)

Equally serious, unlike previous initiative such as New Labour’s post-14 diplomas, potential providers may be wooed by financial carrots (although these should not be overestimated!) but then be forced to back track. Twenty years ago, when GNVQs were repackaged as vocational A levels, taking on many of the characteristics of academic learning, BTEC registrations increased. This time around there may be no BTECs to return to and so students, with nowhere else to go could be forced on to A-level courses. In the form that A-levels currently take, this cannot be good for either staff or students.

Blunkett and Baker are not against the introduction of T-levels, only against the way they are being introduced. Our curriculum aims are completely different to theirs. But as they want to defend BTECs, they might turn out to be useful if surprising allies. (In the case of Baker, particularly surprising). Progressive educators, critical journals and teacher unions need to up their game.

Very well put! But I doubt Baker and Blunkett will make much impression on the government-supported-by-the-media consensus that T-levels lead to jobs for ‘those who are good with their hands, not their heads’ as people want to believe this and also that they may lead to apprenticeships linked to supposed ‘leveling-up’. Even if it does not divide schools lower down at 14+ when pupils were once sorted into sheep and goats for O-levels or CSEs, it will – as you say – ‘short circuit, or at the very least, make further curriculum reform extremely difficult’. In addition, there is David Ridley’s point from Andrew McGettigan that diverting more 16-18s onto Ts is aimed at reducing the numbers of A-level applicants to ‘elite’ or at least ‘academic’ unis and thus cutting back on student fees/ loans, especially now this debt is recorded as capital expenditure by the DoE, ie. comes out of public spending, instead of being written off when not repaid as previously. This implies caps and thus direction on the numbers of applicants different and supposedly independent unis can recruit for their courses. As David writes in the latest ‘Post-16 Educator’, ‘A more slippery way to achieve the same outcome is to put conditions on student loan qualification, such as minimum A-level requirements and, as you say, closing the ‘back door’ to uni entrance represented by BTECs – a route that Ridley adds is ‘often favoured by working-class and BME students’.

I forgot to add that I believe the Association of Colleges is also campaigning against T-levels and that unfortunately, the Labour Party remains committed to them!