As the UKs economic difficulties persist, there’s a continued focus on skill shortages. Most discussions ignore issues of job quality, yet it’s evident that labour supply issues are more visible in jobs deemed ‘low skilled’ with lower wages and poor employment conditions. In otherwords, rather than productivity and increased output being held back by skill shortages in some ‘lovely jobs’ particularly in the tech sectors; there has been far less concern shown about ‘lousy jobs’

But as the labour market tightens and the ‘reserve army’ depletes (and right-wing Tories mobilise for tighter immigration controls) low rates of union organisation and also in some cases, low profit margins of some employers, mean ‘market forces’ can’t be relied on to ensure pay levels increase.

For example, data shows average pay for fruit picking, where shortages abound and which pre- Brexit relied heavily on seasonal Eastern European labour, equivalent to just £22 000 per year. In hospitality (also heavily affected by workers leaving post-Brexit, and now having to rely more on UK student labour) it’s reported that wages across the sector have increased between 8 -12%. While this is higher, it only just keeps up with inflation. Meanwhile in the care sector, where at the end of 2022 165 000 vacancies were recorded and where the Red Wall MPs want reductions in overseas visas – the sector is being propped up by overseas labour – it’s estimated that nominal median care worker pay has only increased by 6% (£0.53 per hour) since March 2022 and the average care worker was worse off, in real terms, by £0.29 per hour (3%) than they were in March 2022 due to high inflation.

But if it doesn’t lead to higher pay, ‘full employment’ (about 1.3 million people are recorded as ‘unemployed’ while there are still more than 1 million vacancies) does allow individual workers struggling at the lower end of the labour market, more choice over what they do and where they work and they can’t be blamed for leaving socially useful work in care homes for socially useless employment in Amazon type organisations.

Meanwhile, the post-pandemic period has seen increases in ‘economic inactivity’ by sectors of the population who, having sampled and experienced life without work have been part of what some have called a ‘great resignation’ (though statistics also show high rates of long-term sickness, a significant amount of this being Covid related, with thousands relying on benefits). Others argue that more and more young people are part of a ‘post-work’ culture, though this is difficult to prove through statistical evidence.

More generally, labour market dysfunctionalities and poor rates of productivity have been intensified by longer term problems of low capital investment in the UK economy particularly and more recently in relation to AI and robotics (in otherwords, employers have relied on supplies of cheap labour instead).

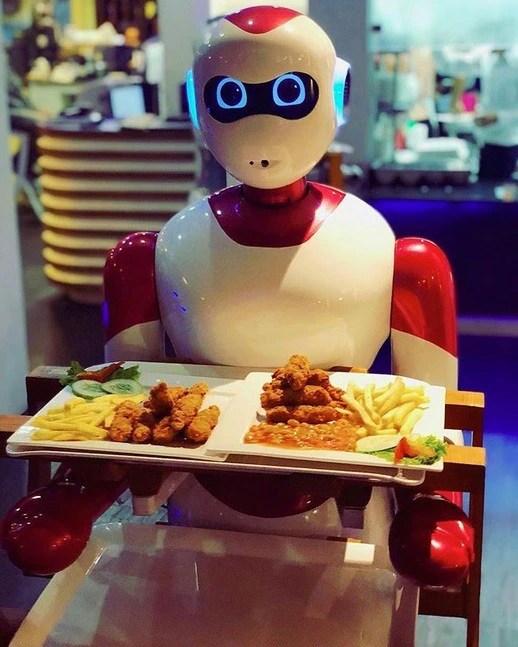

But even though robots might bring your food to the table in a Japanese or South Korean eatery and while many physically exhausting lousy jobs can and should be automated, there will always be others that can’t or shouldn’t be. But people will have be paid properly to do them.

Another informed and clear explanation of realities that should be plain to all those commentators who – deliberately or not – confuse and muddle these basic issues. Further discussion in the latest ‘Post-16 Educator’ with another article by Martin on ‘Education, qualifications and skill’, commenting on David Ridley’s ‘Expensive machines’ article in the previous issue by David Ridley.

Apology, please remove careless repetition of ‘by David Ridley’ in last three words of comment above.

Interesting stats and clear analysis

<

div>

<

div>Do you think having anti-poverty staff