Well before being elected, Labour set out intentions to increase labour market participation. At the centre of its policies, was achieving an 80% participation rate for 18–66-year-olds over a ten-year period, way above the current 75% – though this includes part-time working. ‘Rebuilding’ Britain’s labour force has been the main brief of the Department for Work and Pensions minister Liz Kendall. But as with other departments, the Treasury has always had the upper hand, setting tight spending limits with non-negotiable fiscal rules for borrowing.

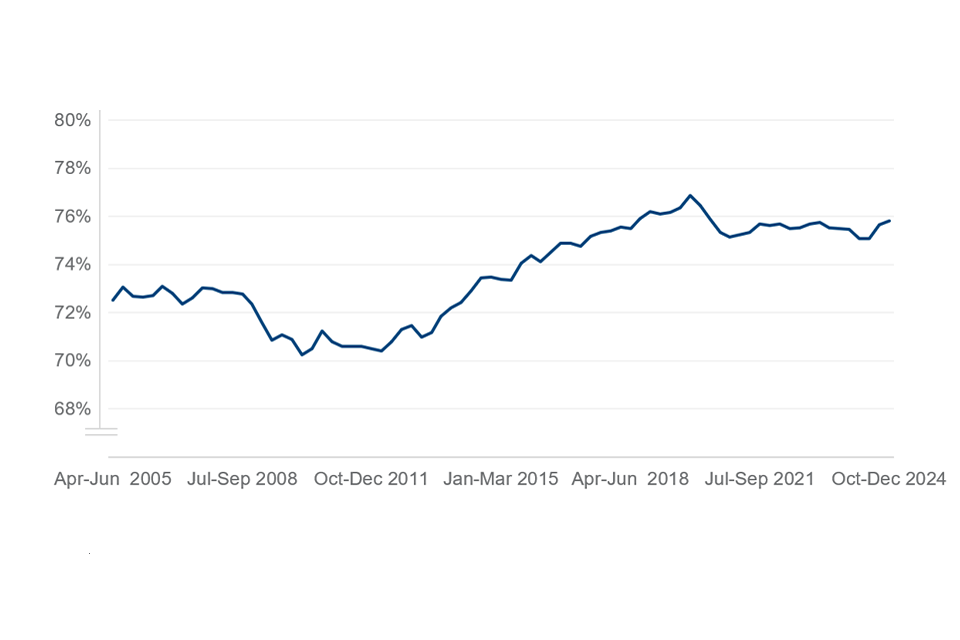

More workers, regardless of what they do, will lead to more output, more output means more growth and more growth means higher standards of living and better, or rather ‘sustainable’ public services, so the logic goes! As the chart shows, participation rates increased rapidly after the financial crash, but they’ve stalled since the pandemic.

With unemployment rates historically low, the boundaries between work and non-work becoming hazier and quickly capitulating to Reform’s demands for ‘British jobs for British workers; like their Tory predecessors, Labour front benchers have become fixated with the number of people ‘economically inactive’ – those not in work, but not actively seeking it.

Rates of economic inactivity have increased substantially since the pandemic, standing at well over 10 million, partly reflecting what’s been termed a ‘great resignation’ where the experience of the furlough resulted in thousands of people, particularly those in late middle age, re-evaluating, but then withdrawing from future labour market participation.

It’s estimated that a million people (many over 50) left the labour force voluntarily but also permanently, post-furlough. As a result, the huge spike in unemployment when the support was withdrawn failed to materialise. Vacancies increased with employers reporting shortages of skilled workers.

Recognising that established employees wouldn’t return, Kendall’s 2024 White Paper Getting Britain Working had a particular focus on NEETs (young people not in education, employment or training) but NEET numbers show little sign of falling and Labour’s ‘Youth Guarantee’ is unlikely to materialise into anything concrete. While 40% of NEETs are classified as being ‘unemployed’, up to a quarter report a long-term health issue, particularly a mental health issue, as the main reason for inactivity.

At the same time, Kendall launched a more general assault on welfare benefits going to people registered as long-term sick, including those claiming Personal Independent Payments (PIPs). The gutting of key parts of the welfare bill has been an embarrassing failure for Kendall’s labour market reforms and heaped massive pressure on Rachel Reeves.

But even before the main contents of the Welfare Bill were gutted, experts were already claiming it would have both a minimal effect on labour market participation – the paltry £5 billion savings from a welfare bill of over £600 billion would also have generated additional social costs and put further pressure on other services.

So, desperate to both expand the workforce, but also claw back money from elsewhere, Kendall and Starmer are now looking to reduce the stream of retirees. The ‘triple lock’ pension protection – a manifesto commitment, could still be abolished and with the increasing cost of pensions (for the year ending March 2024 pensions spending was £202.9 billion – over 7% of GDP – getting on for twice the size of the education budget) there are provisional proposals for the age of eligibility to rise further.

But attempting to force elderly people to remain in the workforce will also be unsuccessful. More probable, greater numbers of pensioners (particularly those without additional sources of income, or not able to release equity from their homes) will instead slide into poverty, putting further pressure on the NHS. Besides, adding older workers to the labour force will not, as the birth rate falls, mitigate the more general fall in the supply of younger workers.

Of course, as the labour market cools, (with unfavourable conditions internationally compounded by Labour’s NI increases) as in the past, they’ll be a growing reserve army of unemployed workers to draw from. But meeting the Chancellor’s obsession with ‘growth’ even with a more relaxed immigration policy, requires far more than just trying to stretch the size of the labour force. The UK’s ‘productivity’ rates (output per worker) are abysmal and GDP per capita has been falling.

Righting both these requires coordinated investment in technology and constructive use of AI to increase workers efficiency rather than oppress them – developing a key role for the public sector in what esteemed economist Mariana Mazzucato has referred to as an ‘Enterprise State’

Increasing output this way, in other words being able to produce much more for much less, would start to create space, but also provide opportunities to raise issues about the about the quality and the type of work (why are there still so many ‘bullshit jobs’?) and under what conditions.