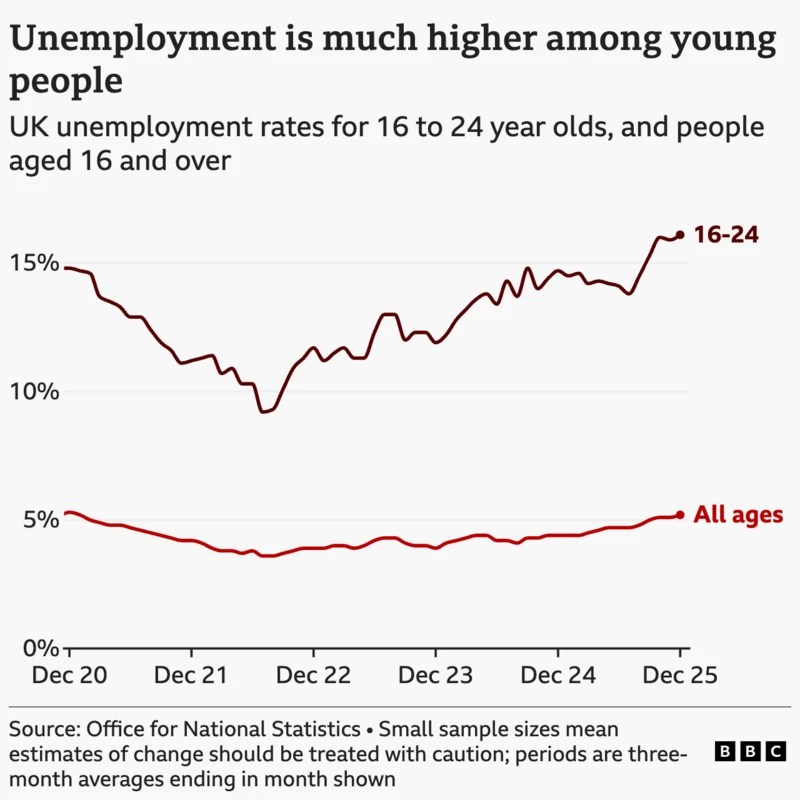

Labour market data released this week shows the UK jobless rate increasing to a post-pandemic peak of 5.2 %. According to the Office for National Statistics, youth unemployment has now reached 16.1% the highest in more than a decade even if it’s always been much higher than unemployment generally.

These numbers for 16–24-year-olds are of course extremely concerning, but it’s the total of 18–24-year-olds ‘not in full-time education or employment’ that gives a more comprehensive picture, as this doesn’t include students looking for part-time work. Unemployment for this category comes out at 13.6% – around 450.000 and is increasing. Business commentators point to rising employer costs, while the Starmer government is considering a reduction in the minimum wage to price young people back in. At best these would be short term solutions to long term problems. Meanwhile ex-Labour minister Alan Milburn has been brought back into to try and fix things.

In recent months however, it’s become common place for political leaders to concentrate on those ‘economically inactive’ – according to the ONS, this figure comes out at 17.3%. Put this with those officially unemployed and 30% of this category are outside of the labour market – approaching 1 in 5 of the entire age group (for the sake of technical expediency this figure can be equated with those who are NEET). Once again, years after our original publication, there’s talk about a ‘lost generation’ and economically inactive young people may now risk their benefits being withdrawn.

Yet large numbers of these young people are not claiming benefits at all. (Figures for last summer show a total of 750,000 on universal credit, but a substantial number, approaching 200,000 of these are working.) While the DWP doesn’t release specific figures, the Resolution Foundation estimates the proportion of young people inactive (and claiming UC) due to sickness or disability is over 1 in 4 (around 250,000). If most of these are only having minimal contact with employment services, based on these estimates, there are also another quarter of a million 18-25 completely ‘off the grid’ – with no systematic way of finding out what they do or how they survive. In total, 45% of under 24-year-old NEETs have never (officially) had a job.

Ministers are desperate to cut the benefits bill, but it’s the concern that sections of Generation Z are detaching themselves from the ‘work contract’ (the post war idea that working hard ‘will get you on’) that really worries ‘the party of labour’ . But rather than raising issues about ‘attitude’ and ‘character’ it would be more accurate to describe this as a detachment from a ‘bad work contract’. This confronts young people generally, as graduates are unable to find work commensurate with their qualifications and increasingly demoralised about having to ‘downsize’ (and by doing so, bumping those with fewer qualifications further down the labour queue).

Worse still, as ‘middle jobs’ continue to disappear and AI creeps in, more graduates end up in ‘precariat’ sectors themselves – trade journals show half the workforce in drinks and restaurants under 24 with 1 in 4 young people starting their ‘careers’ in retail. A crude answer to the question of why there are so many NEETs, might be that there are too many graduates; but a proper answer is that there’s simply not enough good work for young people to transition to. The labour market will need to be run in very different way, if NEETs are to be re-engaged and graduates stopped from tumbling down.

So, with approaching half of young people in the UK now spending over 15 years in full-time learning, will the fact that you increasingly have to run up a downwards escalator undermine the ‘education contract’? If the benefits from attending university are considered to be primarily economic, then the answer would be unequivocally ‘yes’. Yet despite falls in the ‘graduate premium’ the extra labour market return compared to non- graduates, there’s not been hard evidence of a real fall off in home-based applicants. With ‘going to uni’ now becoming an integral part of many young people’s lives (despite the expense) and a growing array of courses covering almost every interest and whim. It’s maybe too early to provide a definitive answer.